National Stop Bullying Day, which is referred to by some as “Unity Day,” is observed annually on the second Wednesday in October. This annual designation is intended to bring awareness of the need to stand up against and put an end to bullying.

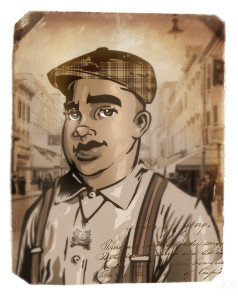

In this excerpt from Piper Houdini: Apprentice of Coney Island, Piper helps Sal Gamache against a bully who is trying to steal an amulet that has great significance to him.

The author at Loew’s Kings Theatre as it exists today.

CHAPTER SIX

The Zombie’s Brother

A skeletal frame of beams, girders, and columns ascended from the torn landscape along Flatbush Avenue. Construction was well underway and the cornerstone had already been laid. But the colder temperatures had forced all work on the building to come to a halt.

There was about three inches of new snow on the ground and clumps of it blemished a sign that children had used as target practice for their snowball fights. On warmer days, the words “Future site of the Loew’s Kings Theatre” could be read on the face of the sign.

Another sign below it read, “Danger: Keep out!”

A boy in baggy tweed pants climbed to the top of the scaffolding where the theater’s marquee had already been erected. Salvador Gamache came here when he wanted to read in peace. He dreamed of being an usher when the Loew’s King finally opened.

That’s because Sal was a “reel boy.” He enjoyed the movies. He had been to some of the other “Loew’s Wonder Theatres” and could imagine the high curved ceilings, ornate walls and windows, and sweeping staircase that would soon define this one.

The Wonder Theaters had been funded by Marcus Loew to establish his preeminence in New York film exhibition. Loew used extravagant ornamentation to create a fantasy environment that would stimulate the imaginations of average citizens by making them feel like royalty.

Every morning before school, Sal would perch atop the marquee and spend a half hour or so reading something by one of his favorite dime-store novelists. It was a cure for his loneliness and an escape from the sound of his parents arguing.

Inside the Loew’s King Theatre.

He would imagine the scenes in his books being played out on the big screen of the movie palace. This morning he was enjoying the latest issue of Weird Tales, in which bug-eyed aliens were plotting to take over the world.

Sal wasn’t allowed to read the pulps at home. His old granmé called it terib—horrible stuff—and warned him that it would stunt his growth and turn him into a socialist.

Sal’s family had moved in with his granmé before the start of the school year. It was always hard being the “new kid” in school. But it was even harder for Sal because he was the new black kid.

Not that he was the only black kid in school. African Americans had been migrating from the South to the big cities since before the Great War. Newspapers claimed that the reason for this “Great Migration” was racial tension and the widespread violence of lynchings in the South. But Sal didn’t know anybody who’d been lynched.

Yes, racial tension was alive and well in Louisiana, just as it was everywhere else. But in the North, black people could find better jobs and attend better schools. It was also a place where his papa could vote!

Sal Gamache as depicted by artist John Kissee.

Unlike most of his fellow black classmates, Sal’s family hadn’t migrated to the North looking for work. His papa earned a steady income from the sugar cane farm he owned outside New Orleans.

The Gamaches had come to New York for medical care. Sal’s older brother Henri had been stricken with a rare brain disorder that had baffled Louisiana’s medical community. The family moved to Brooklyn so that Henri could be treated at Bellevue Hospital, which was well-known for its psychiatric facilities.

Overall, the move had been a good one for Sal. Sure, there were things he missed about Louisiana. But the school he was attending in Brooklyn was definitely a step up. Public schools for black kids in New Orleans weren’t as good as the ones for white kids. In New York, however, there were no “black schools” or “white schools.” Segregation had ended here over 25 years ago.

The same was true about movie theaters. In the South, black people were required to sit in a separate area—usually the balcony, where the view was terrible. But in New York, the theaters were large enough to support black and white audiences without dividing them. That’s another reason why Sal enjoyed reading at the Loew’s King. Even though it wasn’t finished yet, nobody could tell him he wasn’t allowed to be here.

“Hey, you’re not allowed to be here!”

The voice startled Sal so much that he almost tossed his Weird Tales over the side of the marquee.

He looked up. A lanky figure stood between him and the early morning sun. Sal’s eyes took a moment to adjust to the contrast of the dark figure against the bright rays streaming behind it. But his ears had already placed the speaker by the way he pronounced the “here” as “heah.”

“Rand! What are you doing in New York?” Sal exclaimed, his own speech marked by a slight French Creole accent.

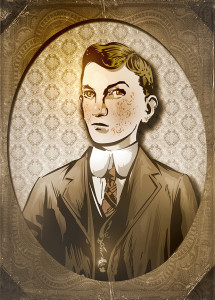

John Rand as depicted by John Kissee.

John Rand crossed his arms over his chest. He had unkempt sandy-colored hair and an ugly serpentine rash on both sides of his face.

“Whatcha reading?” the boy asked, though Sal could tell he didn’t care.

“A magazine.”

Rand tilted the periodical back so that he could read the title.

“Any stories in here about the undead?” Rand probed.

He wasn’t a big kid, but he was bigger than Sal. Well, taller anyway. Sal’s waistline was bigger. He didn’t think of himself as heavyset, but he was heavier than most kids his age. He liked to say that he was “stocky” and blamed it on his mom’s gumbo. But the simple truth was that Sal was not a big fan of exercise.

“What’s it to you?” Sal asked the taller boy.

“My stepdad’s a doctor. Heard all about your family’s little secret. Strangest case he ever heard. No pulse. No breath. Even some rotting flesh.”

“You’re all wet, Rand,” Sal protested weakly.

Rand ignored him.

“But every time the docs wanna pull the plug, your brother gets up, walks around a bit, and performs a few tricks like a dog. Then he goes right back to bed, without saying a word.”

Rand stepped closer to Sal.

“Stranger still, it only seems to happen when you’re in the room, Gamache. What’s that all about?”

The talisman of Baron Samedi.

Sal reflexively stroked a sterling silver amulet that hung from his neck beneath his shirt. The pendant had an image of a cross mounted on a tomb flanked by two coffins.

“That where you keep it?” Rand asked, nodding toward the spot where Sal was groping.

“What the hell are you talking about?” Sal demanded, dropping his hand.

“Don’t play stupid with me, jigaboo.”

Rand reached for the amulet, but Sal knocked his hand away and leaped to his feet.

“Jigaboo? Is that the best you got?”

Sal almost smiled at the irony. The kids in his old school had made fun of him because his skin was too light. Here it was too dark. Sal was actually Creole—a mix of African, French, Spanish, and Native American heritage. Or, as his brother used to say, “We’re a bunch of mutts.”

“Go visit the south, Rand,” Sal said, trying to sound self-confident. “They give lessons in bigotry to ignorant bozos like you!”

Rand grabbed Sal by the shirt and slammed him against a wall.

“You should’ve stayed in the south! You and all your kind!”

Rand dropped Sal to the plywood floor with a fist to his gut. Then he kicked over the brown leather satchel that Sal always carried with him, spilling books everywhere.

Sal had been in plenty of scraps down in Louisiana. But he never took joy in them like some of the boys in the neighborhood gangs. It’s not that he was a coward—he just wasn’t good at fighting. He could take a punch but couldn’t throw one to save his life. Just the thought of his fist connecting with someone’s face—the look, the sound, the feel—was enough to make him puke.

But when Rand started rummaging through his books, Sal felt violated. Something snapped inside him. Rand held up a book entitled The Book of the Dead: The Papyrus of Ani by E.A. Wallis Budge.

“Is this it?” Rand demanded. “Does this tell you how to do it?”

Tightening his fist, Sal leaped at his adversary and socked him in the nose. He heard a crack but wasn’t sure if it was the boy’s nose or his own hand.

“Oww!” they both cried at the same time.

John Rand held a finger to his nose and Sal saw blood dribble onto it. Rand looked at it and then tasted it as if to confirm what his eyes had already told him.

“You dirty dinge!”

Rand raised his fist to return the blow, but Sal twisted his head so it barely grazed him. The failure to connect just made Rand angrier, and his next jab smashed Sal’s lower lip into his teeth. The stocky boy hunched over in pain and he accidentally struck Rand in the chin with his elbow.

Pressing the advantage, Sal lunged at Rand, ramming his head into the boy’s stomach. As Rand fell backward, Sal continued to advance, his lungs heaving with each step.

Rand struck his opponent in the nose with the back of his hand. Sal lost his balance but didn’t fall. He grabbed Rand’s wrist and bit his forearm. The taller boy screamed and pulled his arm away.

“You fight like a girl!” he exclaimed.

“At least I don’t look like one!”

Rand fumed. His eyes darted around at the bits of construction debris that littered the area.

“You’re not the only one who can fight dirty,” he said, snatching up a loose two-by-four and approaching Sal like a demonic samurai.

Sal scampered backward, desperately seeking some kind of protection. His hand fell upon another beam of wood. He raised it just in time to block a swipe from Rand’s wooden scimitar.

Sal took a swing at Rand, but it didn’t connect. The momentum made Sal lose his balance and he collapsed onto the floor.

The next thing he knew, Rand was pouncing on him like a drunken panther. He knelt on Sal’s chest, driving his bony knees into Sal’s ribcage. Rand turned red in the face and the snakes on his cheeks turned purple. But Sal didn’t think it made his adversary look threatening. On the contrary, Rand looked nervous—like he was scared he might actually hurt him.

“Get your lousy knees off my chest,” Sal screamed. He fumbled around him for something, anything, to turn the tide to his advantage. His hand landed in a pile of something soft and gritty.

Sawdust.

He grabbed a handful and threw it into Rand’s face.

“Aggh, my eyes!” Rand exclaimed.

Coughing, spitting, and sputtering, he blindly groped for Sal’s throat.

Sal turned his head to the side and he felt a tug at the frayed leather band around his neck. It snapped. Before either of them could react, the cord slithered down Sal’s neck, slipped between two wooden planks, and fell to the slushy sidewalk below.

Rand scrambled to his feet and ran toward the construction ladder that both boys had used to reach the top of the awning. Sal reached out with his foot and tripped the fleeing youth. He clambered over Rand to reach the ladder first. But Rand blocked him with a knee to the groin and Sal doubled over in pain.

Rand’s victory, however, was short lived. Sal teetered for a moment and then collapsed seat-first onto his face.

“Get off me, lardbutt!” Rand’s muffled voice demanded. He kicked and swatted at the heavier boy, but Sal didn’t budge.

Just then, the adversaries heard the sound of two delicate hands clapping in mock applause.

“Congratulations, boys,” said a girl’s voice. “That had to be the most pathetic fight I’ve ever seen.”

The first thing that Sal noticed was the girl’s hair. It looked like it belonged on a Raggedy Ann doll. She wore a brand-new houndstooth jacket and a black panne velvet skirt that gathered at her knees. Sal could tell by the way the girl fidgeted that she was as comfortable in her clothes as a baby in burlap. But at least her clothes were more flattering than the flapper duds most of the girls in school were trying to get away with.

The redhead was holding a Grape Nehi in one hand and twirling a familiar charm by its leather cord in the other.

“The amulet!” they exclaimed.

“Is this what you boys were fighting over?” she asked.

Sal rolled off Rand’s face and both boys jumped to their feet.

“It’s mine!” Rand proclaimed. “The spade stole it from me!”

“That’s exactly what I figured,” the girl said, giving Sal a dirty look. She palmed the amulet and handed it to Rand. The boy stuck his tongue out at Sal.

“No, wait! It’s mine!” Sal protested.

The girl ignored him and pressed the object into Rand’s palm, closing his fingers around it. She held the blond boy’s eyes with her own.

“The cord is ripped. So put it in your pocket and keep it there until you get to wherever it is you’re going.”

Rand nodded and stuck his fist into his pocket. He turned and scampered down the ladder, giving Sal a wink on his way down.

“So long, sucker!” he taunted before disappearing beneath the edge of the marquee’s roof.

Sal groaned.

“Are you all right?” the girl asked.

“Of course I’m not all right!” he replied.

His chest hurt like hell and his nose was bleeding. He touched the tip of his tongue to a cut on his lip and winced. Speaking only aggravated it.

The girl scooped up a bit of snow and pressed it to Sal’s swollen lip.

“Ow!” he yelled, knocking her hand away. “Whadja do that for?”

“I thought it might help the swelling. And stop the bleeding.”

Sal didn’t reply. He was too busy trying to catch his breath. Rand had been right about one thing—he was definitely out of shape.

“Well, at least wash your face with it,” the girl said.

She snatched his wrist, turned his hand up, and plopped the snow into his open palm.

“Stop pretending you care,” Sal said with a scowl. “You gave that cake-eater my pendant! Us colored boys are always the bad guy, right?”

The girl smiled and opened her hand.

“Not always. Sometimes pale-skinned redheads make better thieves.”

Sal’s pendant dangled from her finger on its leather thong like a yo-yo string on a string.

“My amulet!” Sal cried out. “How did you…?”

“A little sleight-of-hand my uncle taught me,” she boasted.

“If that’s the amulet then what’s in Rand’s pocket?”

The girl took a swig of her Nehi. She drained the last drop of the bubbly refreshment, wiped her mouth with her sleeve, and turned the empty bottle upside down.

“They should really come up with a way to make these things re-sealable,” she said, circling the bottle tip with her finger. “Otherwise you gotta finish the whole darn thing.”

“The cap!” Sal beamed. “But then, how’d you know the pendant was mine and not his?”

“I’ve seen lots of fights in the places I grew up,” the redhead replied. “I can tell when someone’s fighting to take something and when someone’s fighting to keep it.”

She handed the amulet to Sal.

“Thank you,” he smiled gratefully.